Explore Waikīkī’s fascinating evolution, from its royal heritage and historic battle to its emergence as a world-renowned beach destination.

A shortlist unveiling the pivotal moments that shaped present-day Waikīkī. From the settlement of the wetlands and the battle for the Hawaiian Kingdom to the rapid development of Waikīkī and the rise of tourism, here are the must-know moments in Waikīkī’s nearly 2,000-year history.

Table of Contents

- 1. Polynesian Pioneers: The First Settlers of Waikīkī (1000-1200 CE)

- 2. Hawaiian Ingenuity Drives Agricultural Boom (1200-1600 CE)

- 3. Waikīkī’s Golden Age: The Reign of the Māʻilikūkahi Dynasty (1400-1800 CE)

- 4. Hawaiian Kingdom: The Rise of the Kamehameha Dynasty (1795-1874 CE)

- 5. Disease & Disruption: Waikīkī’s Food System in Decline (1778-1900s)

- 6. The Royal Era of Waikīkī (1795-Early 1900s)

- 7. The Māhele: Land Reform & the Shift to Commercial Land Use (Mid 1800s)

- 8. The Plantation Era: Impact on Hawaiʻi’s Economy & Waikīkī (1835-2016)

- 9. Reclaiming the Wetlands: From Taro to Tourism (Early 1900s)

- 10. Waikīkī’s Emergence as a Global Tourism Hotspot (Late 1800s)

1. Polynesian Pioneers: The First Settlers of Waikīkī (1000-1200 CE)

The first human footprints on the sands of Waikīkī belonged to Polynesian voyagers who ventured from the Marquesas Islands and Tahiti. These skilled navigators crossed the vast Pacific Ocean in their canoes, arriving in waves as early as 300 CE. They gradually settled along the islands’ coasts and valleys, with the earliest known settlement in Waikīkī emerging around 1000 CE, near what is now the Halekūlani hotel.

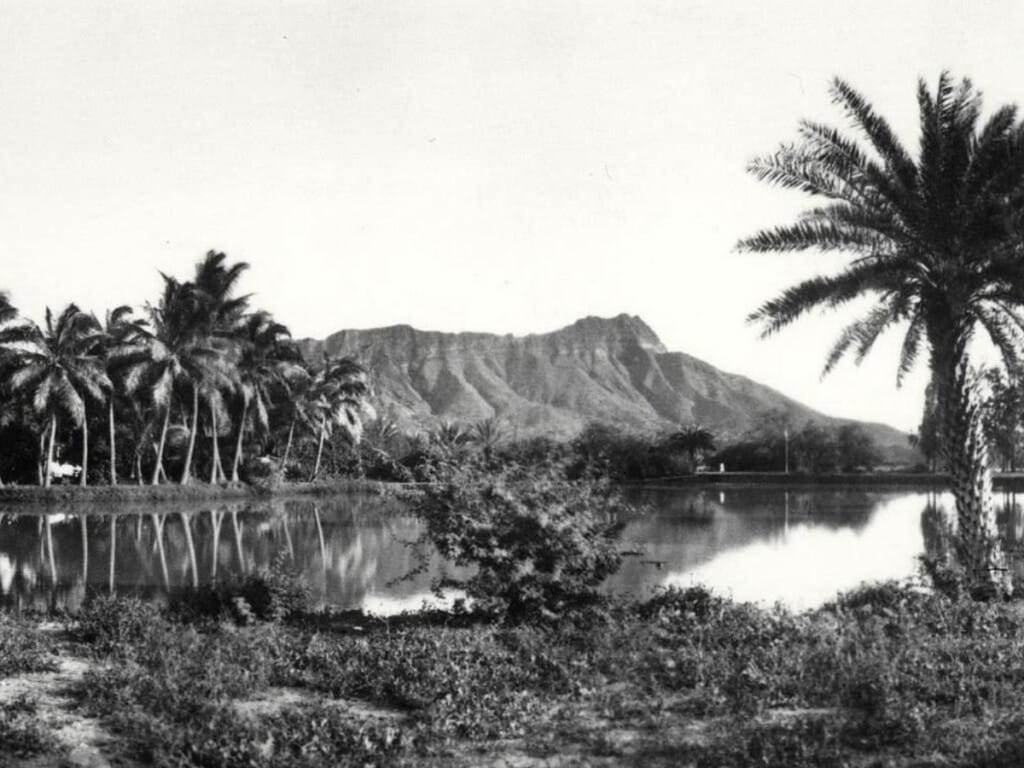

Waikīkī was so different back then! Gazing up from the shore, these early settlers would have been met with an unobstructed view of mountains rising in the distance, crystal-clear streams cascading down lush valleys and freshwater springs scattered along the plain. This idyllic landscape, a far cry from the bustling tourist destination it is today, was named “Waikīkī” by early Hawaiians, meaning “spouting water.”

These resourceful settlers were not merely gifted navigators; they were also agricultural pioneers. They brought with them crops that would transform the Waikīkī landscape and become staples in the Hawaiian diet. Among these were kalo (taro), ulu (breadfruit), niu (coconut) and maiʻa (bananas). The cultivation of these crops, combined with their expertise in fishing and gathering, allowed them to develop a thriving food system in their new island home.

2. Hawaiian Ingenuity Drives Agricultural Boom (1200-1600 CE)

As Hawaiian settlements expanded in Waikīkī, the community transitioned from small family farms to large scale agriculture. In the 1400s, the High Chief Kalamakua, a prominent kalo farmer, spearheaded the construction of extensive loʻi kalo (taro patches) and an intricate irrigation system.

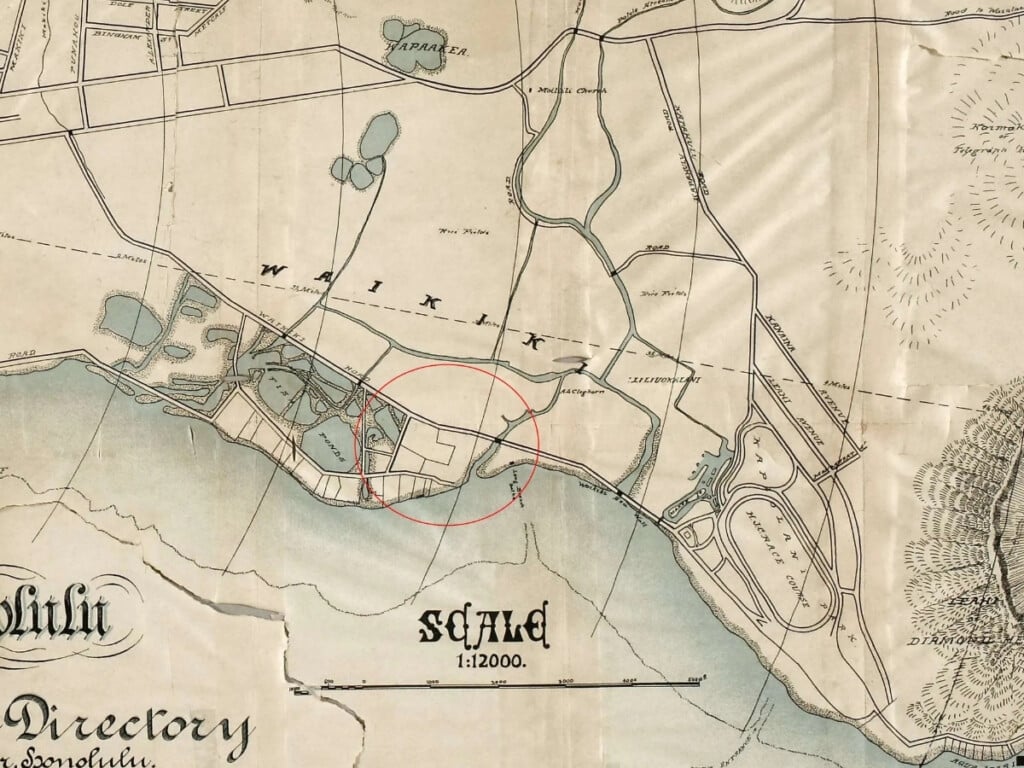

By the mid-1500s, the expansion of agriculture in Waikīkī led to a significant population increase. With a growing workforce, the community embarked on another ambitious project: the construction of loko iʻa (fishponds). One of the most renowned, Kaʻihikapu, was built by Kalamakua’s descendants on present-day Fort DeRussy.

While it’s impossible to quantify the amount of food produced in 15th century Waikīkī, it’s clear that Hawaiian ingenuity in agriculture and aquaculture led to a thriving food system. By the late 1700s, over 400 fishponds were operating across Hawaiʻi, producing two million pounds of fish annually.

Modern development has largely obscured Kalamakua’s food system, but remnants of his legacy persist. Land records reveal that some of his kalo patches, such as Keokea and Kualulua (near the Ala Wai Golf Course) and Kalamanamana (close to ʻIolani School), were still in use in the 1800s. These kalo patch names became permanent place names in Waikīkī, serving as a tribute to Kalamakua’s vision.

3. Waikīkī’s Golden Age: The Reign of the Māʻilikūkahi Dynasty (1400-1800 CE)

Waikīkī’s organized network of kalo patches and fishponds transformed the wetlands into a thriving kalo growing and fishing community. This abundant food supply created the conditions for political stability, a fact not lost on 15th century High Chief Maʻilikūkahi. Recognizing the strategic advantage, he relocated his royal court from the traditional seats of power in Waialua on the North Shore and ʻEwa out west, to Waikīkī.

Maʻilikūkahi’s first major act was to establish the ahupuaʻa or land division system, dividing Oʻahu into six districts, each overseen by a high chief. The ahupuaʻa of Waikīkī stretched far beyond today’s tourist zone, encompassing thousands of acres from Honolulu to Hawaiʻi Kai. Waikīkī quickly became the undisputed center of political and economic power on Oʻahu.

The Maʻilikūkahi Dynasty reigned for another 400 years. High Chief Kākuhihewa, a notable descendant who unified much of Oʻahu, oversaw the planting of the coconut grove at Helumoa (now the site of The Royal Hawaiian resort) in the late 1600s. Another prominent descendant, High Chief Kūaliʻi, enacted the compassionate Kolowalu Law, mandating feeding and caring for the needy. The contributions of the Maʻilikūkahi Dynasty further cemented Waikīkī’s prominence, leaving a lasting impact on the island’s political and social landscape.

4. Hawaiian Kingdom: The Rise of the Kamehameha Dynasty (1795-1874 CE)

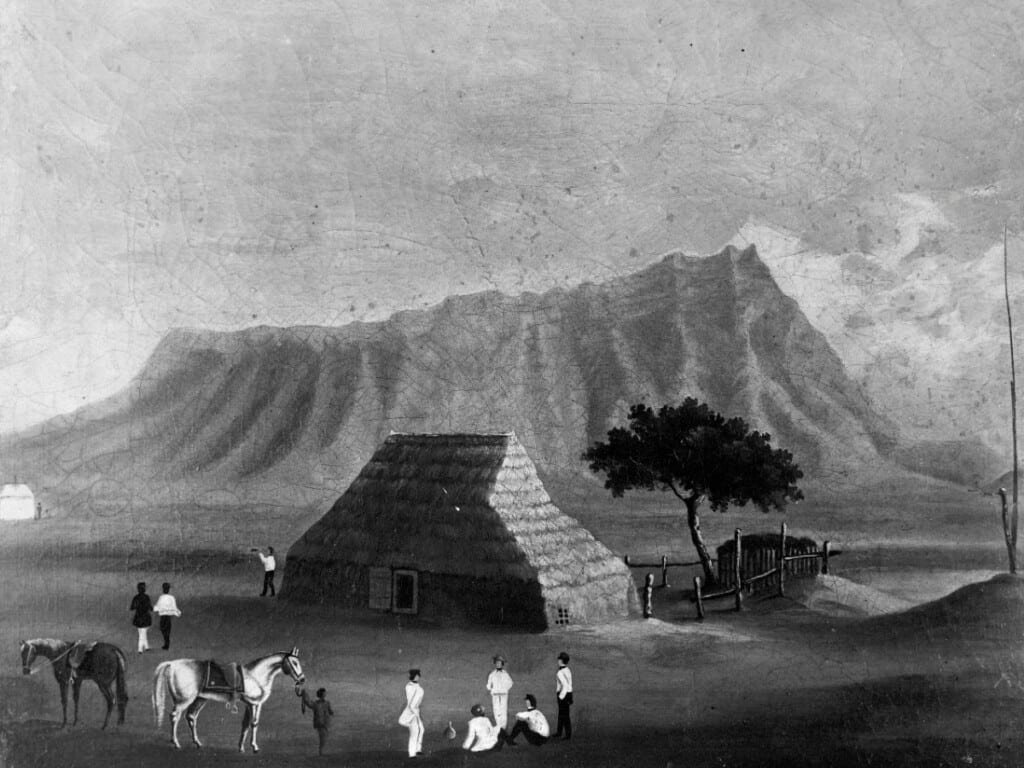

By the late 1700s, Oʻahu chiefs found themselves facing a formidable threat. First came Maui’s army under the command of the High Chief Kahekili, who conquered the island in 1783. Then came Hawaiʻi Island warriors led by the High Chief Kamehameha I. The invasions marked a notable period of interisland warfare in Hawaiian history, and Waikīkī was at the very center of the action.

In 1795, Kamehameha landed at Waikīkī with hundreds of canoes and more than 10,000 soldiers. His warriors set up camp along the sands of Waikīkī Beach near the coconut grove at Helumoa (The Royal Hawaiian resort). From this strategic location, his soldiers gathered supplies and meticulously planned their assault on Oʻahu forces led by High Chief Kalanikūpule.

The decisive Battle of Nuʻuanu ended with Kamehameha’s army pushing Kalanikūpule’s warriors over the cliffs. This was a pivotal victory in Kamehameha’s quest to unify the Hawaiian Islands under his rule. Following his triumph, Kamehameha decided to make Waikīkī his home and the capital of the newly established Kingdom of Hawaiʻi.

Kamehameha and his descendants would reign over the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi for nearly 80 years, ushering in a period of substantial change in Waikīkī and across the Hawaiian Islands.

5. Disease & Disruption: Waikīkī’s Food System in Decline (1778-1900s)

Waikīkī was in a state of post-war recovery when the first known epidemic struck its shores. Thousands of King Kamehameha’s soldiers contracted cholera-like illness while preparing for the invasion of Kauaʻi at Helumoa. The 1804 epidemic halted the invasion and claimed an estimated 5,000 to 10,000 lives.

The arrival of Europeans, beginning with Captain James Cook in 1778, introduced new diseases like influenza, measles and smallpox to Hawaiʻi. Unfortunately, Hawaiians had no immunity to these illnesses, leading to a 90 percent decline in the population. Despite these challenges, the Hawaiian people demonstrated remarkable resilience.

In response to the cholera epidemic, King Kamehameha gathered his most talented medical healers for instruction from Western physicians on combating infectious diseases. When the smallpox epidemic struck Waikīkī in 1853, a makeshift hospital was established near present-day Kapiʻolani Park to care for the sick. By the 1850s, King Kamehameha III created the Kingdom’s Board of Health and the first hospital was built five miles away.

This devastating loss of life had a profound impact on Waikīkī. With a diminished workforce, maintaining the region’s infrastructure became more difficult. Irrigation ditches fell into disrepair, taro patches were covered in weeds and the once-thriving food system faced disruption.

6. The Royal Era of Waikīkī (1795-Early 1900s)

Even as the landscape began to evolve, Waikīkī remained a cherished retreat for Hawaiian royalty.

Imagine King Kamehameha working in the taro patch outside his residence, near today’s OUTRIGGER Waikīkī Beach Resort. King Lunalilo, seeking respite from the pressures of the throne at his estate in Kaluaokau (now the site of the International Market Place). King Kamehameha V escaped the summer heat in his cottage beneath the shade of the coconut groves at Helumoa (The Royal Hawaiian resort).

Queen Liliiʻuokalani, the last reigning monarch of Hawaiʻi, entertained guests at her cozy seaside cottage, “Kealohilani,” near present-day Kūhiō Beach. Her niece, Princess Kaʻiulani, delighted in the sight of peacocks freely roaming the grounds of her family’s estate, “ʻĀinahau,” just a few blocks inland from the Sheraton Princess Kaʻiulani hotel.

The last royal retreat to grace Waikīkī was the stunning home of Prince Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole, built in 1918. “Pualeilani,” boasting breathtaking ocean views, stood near the Moana Surfrider hotel. Today, a historical marker commemorates the site of this regal residence, and the surrounding area is lovingly known as Kūhiō Beach Park.

While the structures themselves may have vanished, the legacy of these royal landowners and their beloved Waikīkī retreats live on in surrounding street names.

7. The Māhele: Land Reform & the Shift to Commercial Land Use (Mid 1800s)

The mid 1800s witnessed a major turning point in Waikīkī’s history with the introduction of land reforms. Landmark legislation known as the Great Māhele aimed to transition landownership in Hawaiʻi from communal to private. This granted makaʻāinana (commoners) the right to claim ownership of land their families cultivated for generations.

Under the Māhele, over 3,200 acres in Waikīkī were granted to 250 individuals. However, most grants awarded to makaʻāinana were relatively small, often less than an acre. While a substantial portion of Waikīkī’s prime real estate was claimed by six members of the Hawaiian royal family.

The consequences of this land redistribution were far-reaching. Many royals who received land grants died without heirs, leaving their properties vulnerable to subsequent claims. Simultaneously, deadly diseases and a decline in traditional subsistence agriculture substantially impacted makaʻāinana, making it increasingly difficult to maintain their land holdings.

The introduction of private property fundamentally altered the perception of land in Hawaiian society. Land, previously valued primarily for its agricultural productivity, now became a commodity for financial gain. This shift in land ownership and values set the stage for the rapid development of Waikīkī into a tourist destination, profoundly transforming the landscape and the lives of its inhabitants.

8. The Plantation Era: Impact on Hawaiʻi’s Economy & Waikīkī (1835-2016)

Kalo was still the king of the crops in Hawaiʻi when the first sugar plantation was established in 1835 on Kauaʻi. But the sugar industry grew to dominate Hawaiʻi’s economy for more than 150 years with the last plantation closing on Maui in 2016. The plantation era fostered economic growth, laying the foundation for sectors like tourism. Sugar production also spurred transportation improvements (e.g. harbors, railroads, roads) that increased Hawaiʻi’s accessibility to the world.

While sugar’s direct impact on Waikīkī is limited, one notable exception was the rise of rice cultivation by the Chinese immigrant population. They repurposed unused taro patches and fishponds into productive rice fields and duck ponds. By 1892, Waikīkī boasted more rice paddies than anywhere else in the islands. Duck farms were also scattered along the shoreline from Waikīkī to Moanalua.

Rice production in Hawaiʻi gradually declined in the late 19ᵗʰ century, and 20ᵗʰ century, as the sugar industry emerged as the dominant force in the Hawaiian economy. While the sugar industry itself may not have directly impacted Waikīkī’s agricultural landscape to the same extent as rice cultivation, its broader economic and social impacts were crucial for the emergence of Waikīkī as a major tourist destination.

9. Reclaiming the Wetlands: From Taro to Tourism (Early 1900s)

The Waikīkī we know today, a vibrant tapestry of high-rise hotels and bustling beaches, is distinctly different from its past. The overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 shifted political power from Hawaiian control to American interests. This change contributed to a substantial transformation of the Waikīkī landscape.

The arrival of the U.S. Army accelerated this change. The Army acquired 70 acres in Kālia in 1904 to establish a military reservation named Fort DeRussy. The kalo patches and fishponds of Kālia had been disrupted by the 1866 construction of Waikīkī Road (now Kalākaua Avenue), which led to stagnant wetlands that bred mosquitoes and emitted foul odors.

The Army began filling in fishponds and draining wetlands in Kālia. They pumped fill from the ocean to build up an area on which structures could be built. This became a model for the rest of Waikīkī.

The wetlands of Waikīkī were declared a health hazard in 1906 and underwent massive reclamation. All ponds and irrigated fields were drained and filled, and the Ala Wai Canal was built to help drain the wetlands. This transformation brought an end to centuries of subsistence agriculture and facilitated the development of Waikīkī into a vibrant tourism industry.

10. Waikīkī’s Emergence as a Global Tourism Hotspot (Late 1800s)

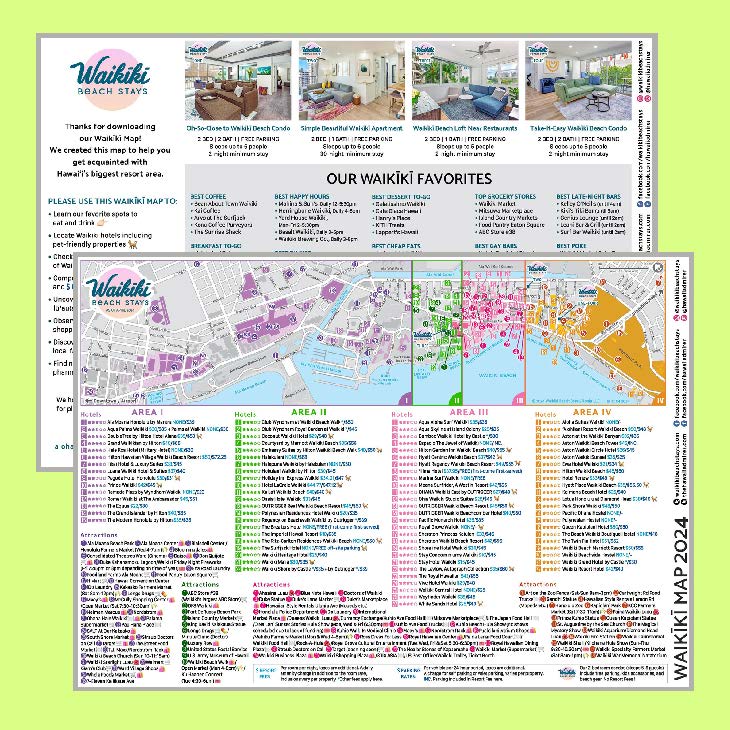

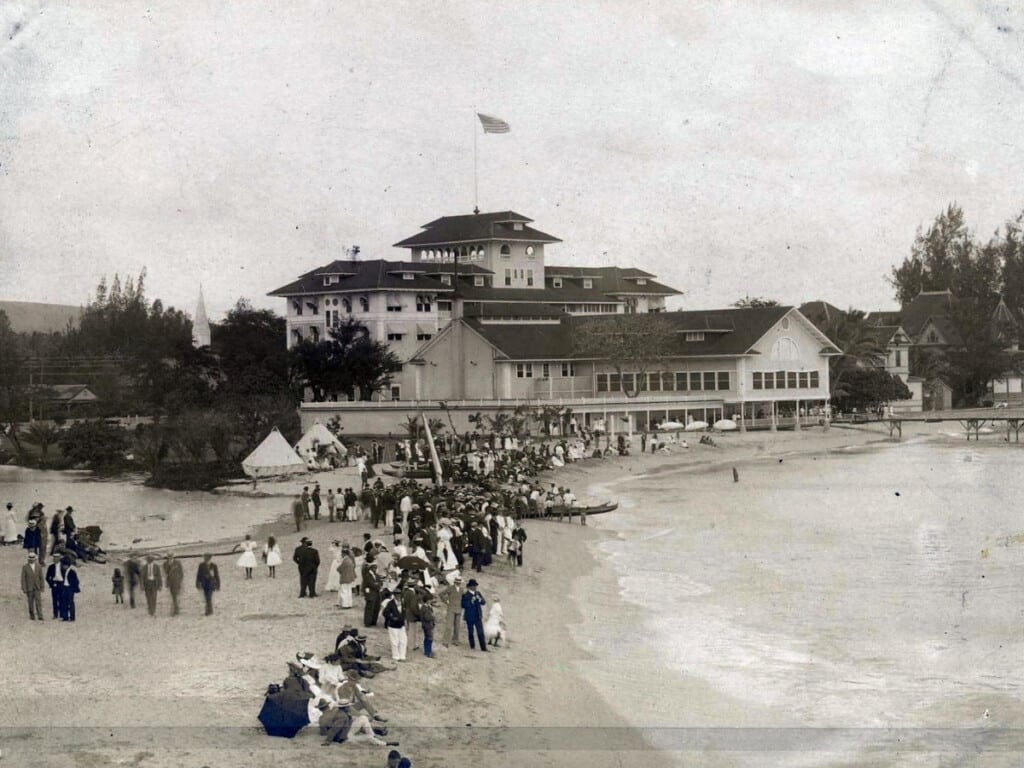

Before the Waikīkī skyline was dominated by towering hotels, the shoreline was dotted with humble bathhouses. These early establishments, initially simple changing rooms for sea bathers, gradually evolved into overnight accommodations. By 1888, Waikīkī’s first seaside hotel, the Park Beach Hotel opened on the site of today’s Elks’ Club. Early hotels like the Moana Hotel (1901) and Royal Hawaiian Hotel (1927) played a pivotal role in establishing Waikīkī as a prominent tourist destination.

During World War II, Waikīkī’s hotels were converted into military housing and R&R centers, while Fort DeRussy was fortified with coastal defenses and beaches lined with barbed wire. Though tourism paused, thousands of military personnel experienced Waikīkī during their service — planting the seed for its post-war popularity as many later returned with their families.

The economic boom in the U.S. after World War II, coupled with the advent of commercial air travel, fueled a surge in tourism. The Hawaiʻi Visitors Bureau strategically marketed the islands to a travel-hungry public, building upon the success of the radio program “Hawaiʻi Calls!” (1935-1975), which romanticized the islands for millions. Elvis Presley’s 1973 “Aloha from Hawaiʻi via Satellite” concert showcased stunning views of Waikīkī to an estimated 1 billion viewers worldwide. This global exposure made Waikīkī a must-see destination.

Waikīkī, with its pristine beaches and burgeoning tourism infrastructure, quickly solidified its position as a premier international tourism destination — a reign that continues to captivate visitors from around the globe today. Of the nearly 10 million visitors to Hawaiʻi in 2024, at least half visited Waikīkī.

Please Follow Us @WAIKIKIBEACHSTAYS

READ NEXT